The science behind an iPhone dumb phone.

← back ——— Harrison Broadbent, published July 9 2024In this article, I explore recent scientific research supporting the tactics I’ve previously discussed for dumbing down your iPhone.

Dumbing down your phone can lead to benefits like improved attention, reduced stress and depression, improved wellbeing and reduced anxiety.

Table of Contents

Recently, I published Turn your iPhone into a dumb phone. Hacker News seemed to enjoy it and there was a lot of discussion.

The same question kept appearing though — why? Why dumb down an iPhone? Why hamstring our most personal computer?

Why? Simple. Our relationships with our phones are terrible. Some of you might pass a day with ~2 hours of screen time and feel pretty good about yourself. Others are in the midst of a 8+ hour doomscrolling session (a regular occurrence for them). Regardless, there’s a growing wave of research on smartphones, problematic smartphone use (PSU), depression, anxiety and addiction. Broadly, our smartphones tend to make us feel anxious, stressed, they continuously distract us and more.1

Fortunately, there’s also growing research on tactics for wrangling your phone usage, which is what I wanted to dig into in this article.

This article connects the research I’ve been exploring to the suggestions in Turn your iPhone into a dumb phone. It’s been a fascinating deep-dive, if not a bit scary (our phones really are pervasive in our lives).

In short:

- disabling notifications can relieve stress and improve focus,

- deleting apps (namely social media) can improve well-being and reduce depression,

- grayscale mode can reduce anxiety,

- plain wallpapers and homescreens also aim to reduce anxiety.

This article breaks down these tactics with references to studies supporting them.

preface

I want to share a high-level overview of how each tactic tries to reshape your smartphone relationship. I think it will be helpful context before we zoom into them individually.

Almost all “tactics” for regulating your smartphone usage do one of three things. They either make using your smartphone less appealing, disruptive or habitual:

- Less appealing — the notion that making your phone less flashy and attractive will help you regulate your usage; the “pull” won’t be so strong.

- Less disruptive — reducing how often your mind wanders (or is dragged) to your smartphone, disrupting your focus.

- Less habitual — short-circuiting the reward-loops in your smartphone by either opting out of them entirely, or nullifying their “reward” aspect.

Be warned — smartphone usage is a tricky, often messy topic. The research tends to be limited in some way (for instance, it’s difficult to gather a large group of people willing to stop using their phones for a while), which makes it tricky to tease out strong insights.

Alongside that, people absolutely get some benefits from using their smartphone. It’s not all bad! It’s just that, overall, the net outcome of our smartphone interactions seems to be, overall, detrimental. It’s a tricky distinction which muddies the discourse.

Regardless, I think you’ll find each tactic and its studies fascinating. Let’s dig in.

A note on the “Screen Time” feature and app blocks:

Research tends not to focus on using features to limit screen time since they’ve been identified as rather ineffective at actually reducing screen time 2. That’s not to say that they can’t be helpful; I see people having wild success with it on Reddit. As a general tactic though, it seems harder to implement effectively (compared to the others here).

disabling notifications can relieve stress & improve focus

We’ve all been there — in the middle of an important task, deep in that delicate, delicious flow, when all of a sudde— bzz. A notification comes through, your phone lights up, and your focus? Ruined.

Smartphone notifications have been found — unsurprisingly — to “significantly disrupt performance on attention-demanding tasks”3. Given it takes ~23 minutes to regain lost focus 4, just a handful of naughty notifications can completely upend your would-be productive morning. We’ve all had those mornings, the ones that got away. The ones where we could’ve got so much done, if we hadn’t kept getting distracted.

As a class of distractions, notifications are particularly good at foiling our focus. The notifications themselves are brief. Just a small ping. By their very nature though, they prompt us with new information, opening the floodgates to related — and very distracting — thoughts, which continue long after the initial ping fades3.

There’s more.

Merely having your phone near you with the *potential* to notify you can be almost as distracting as actually being notified!3 Take a second to think about that — the anticipation of receiving a notification can be just as distracting as the notification itself! I know I’ve felt that anticipation before. Have you?

That’s the power your unchecked smartphone holds over you. Disabling notifications can be one of the best ways to reign it in and regain some of your attention.

Fortunately, this first tactic not only has a large upside (regaining attention), but it’s simple to implement and easy to stick with. You disable notifications for your apps once, then you’re done. A recent study noted that 98% of people who disabled notifications kept them disabled5.

If disabling most notifications entirely is too confronting, you could also try batching your notifications into a scheduled summary which helps in a similar way, without leaving you blind6.

On iOS you can adjust your notification settings in

Settings>Notifications.

deleting apps (namely social media) can improve well-being and reduce depression

In their own way, each app on your phone is a nudge, a tiny fishhook trying to score a catch on your brain and attention. At a high-level, this tactic reduces the number of apps nudging you by simply deleting them. Deleting an app removes its fishhook entirely, helping you stay focused and avoid distraction.

Social media is a particularly wily beast, almost a class of its own. Limiting your usage to 30 minutes per day (or cutting it out entirely) has been linked to significant self-reported measures of well-being and declines in depressive symptoms7.

Completely giving up social media is scary! If it’s too much for you, a common stepping-stone is to remove social media from your smartphone and access it via a computer instead. This lets you check it occasionally, but it’s not a constant firehose of information. Instead, it’s an irregular, occasional trickle, which is easier to regulate.

grayscale mode can reduce anxiety

Switching your iPhone to grayscale mode has been found to significantly decrease self-reported anxiety (by about 30%) alongside PSU and screen time5.

That’s a pretty huge decrease for a single tactic!

The theory behind this tactic is that a grayscale phone is less gratifying5 and thus less engaging. Our phones just aren’t as exciting to use when all the flashy colors are removed. When your phone’s less engaging, it’s easier to control your usage (and not get sucked into a doomscrolling session so easily).

Anecdotally, I’ve oscillated my iPhone between grayscale and color mode for a few weeks now and I agree with the findings. When it’s in grayscale mode, I feel less anxious and engaged with my phone, and it’s easier to put down.

This tactic does have a catch though — it’s hard.

Studies typically find only 30-50% of their participants manage to stick with a grayscale display mode5 1. Most people simply give up when it makes their phone more difficult to use (which is the whole point!) and miss out on the benefits.

If you’re interested in setting up grayscale for yourself, it’s easy. From the grayscale tactic in my previous article, just visit

Settings > Accessibility > Accessability Shortcutswhere you can enable theColor Filtersoption. By default, this will let you enable grayscale mode by triple-clicking your iPhone’s power button. It also lets you switch back to color mode with another triple-click.To enable grayscale directly (maybe you’re using the shortcut already), you can do that in

Settings > Accessibility > Display & Text Size > Color Filters > Grayscale.

plain wallpapers and homescreens also aim to reduce anxiety

Although plain wallpapers and homescreens haven’t been formally studied (that I know of), their aim mirrors the grayscale tactic — they try to make your iPhone less satisfying to use.

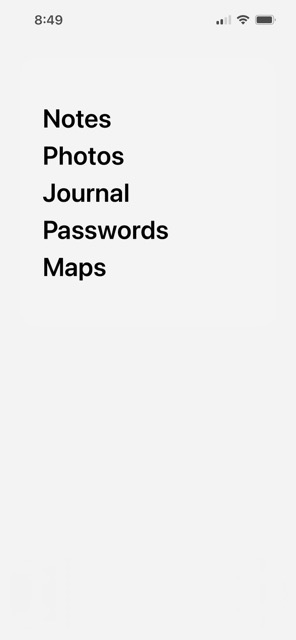

Compare these two screenshots —

|

|

Which do you find more engaging?

If you unlock your phone and see the second example, there’s not much to distract you. Compare that to the first, where you’re assaulted with colours and notifications each time you unlock your iPhone, and you start to see the appeal of this tactic. These tweaks work in tandem to reduce the number of nudges on your phone’s homescreen.

Again, anecdotally, I’ve used this tactic for a few weeks now and I’m enjoying it. Unlocking my iPhone has become quite serene — just a plain wallpaper and a few apps on a list.

This tactic’s caveat is that your smartphone’s app drawer is a single swipe away. No matter how plain your homescreen is, if you’re a swipe away from chaos, its effectiveness will be limited.

That’s OK though, since this tactic doesn’t have to exist in isolation. I think this tactic works best if you also declutter your phone and delete as many apps as you feel comfortable with (and then some, especially social media).

conclusion

I wanted to write this article the instant I published How to turn your iPhone into a dumb phone.

I wanted to show you that these tactics aren’t just my musings. They’re tactics that have, and continue to be, actively studied as methods to reduce the adverse effects our smartphones have on us, with real results to back them up.

One final thing — read the papers!

They’re referenced throughout this article and below; I’ve picked just a handful of the most interesting and relevant ones, and they’re easy enough to parse as a layman. I’ve really enjoyed reading the papers behind these tactics while researching this article, and if you’ve made it this far, you probably will too.

sources

-

A Nudge-Based Intervention to Reduce Problematic Smartphone Use: Randomised Controlled Trial, International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-022-00826-w. ↩ ↩2

-

Consumers Are Happy to Monitor but Unlikely to Reduce Smartphone Usage, Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, https://doi.org/10.1086/714365 ↩

-

The attentional cost of receiving a cell phone notification, Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, https://doi.org/10.1037/xhp0000100 ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

How Long It Takes to Get Back on Track After a Distraction, Lifehacker, https://lifehacker.com/how-long-it-takes-to-get-back-on-track-after-a-distract-1720708353 ↩

-

Color me calm: Grayscale phone setting reduces anxiety and problematic smartphone use, Current Psychology, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02020-y ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

Batching smartphone notifications can improve well-being, Computers in Human Behavior, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.07.016 ↩

-

No More FOMO: Limiting Social Media Decreases Loneliness and Depression, Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2018.37.10.751 ↩